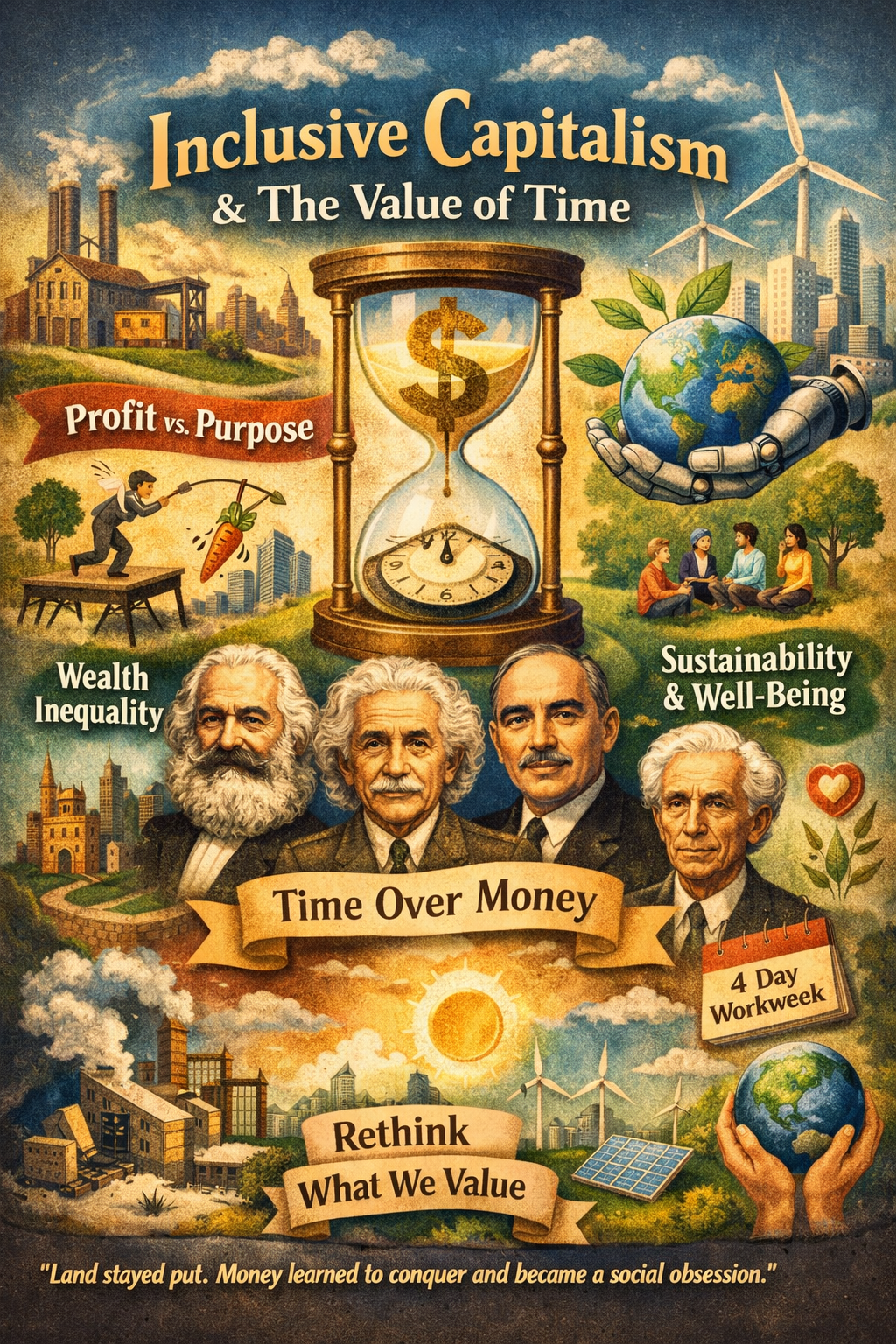

Value Is a Choice, Inclusive Capitalism Is the Correction

Every economic system is defined by what it chooses to treat as value. Feudalism measured land. Industrial capitalism measured money. Late‑stage capitalism now measures money faster than reality can keep up. Capitalism’s defining metric, money, has ceased to function as a reliable nominator of value because it has detached itself from productivity, human experience, and social well-being. When the metric fails, optimisation becomes destructive.

As biologist Edward O. Wilson warned,

“We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology. And it is terrifically dangerous, and it is now approaching a point of crisis overall.”¹

This synthesises the fundamental challenge: our social and economic systems lag behind our technological capacity, and capitalism’s fixation on profit accelerates that mismatch.

This is worth repeating: The current system prioritises profit at the expense of societal and environmental well-being. In short, it prioritises money at the expense of sustainability in the never-ending quest for higher growth.

Inclusive capitalism emerges not as a moral upgrade, but as a structural correction. It recognises that when a system’s measurement no longer reflects lived reality, optimisation no longer promotes stable or equitable outcomes. Inclusive capitalism expands the definition of value to include stakeholders, long-term outcomes, and human well-being, thereby addressing the systemic distortions created by prioritising money above all else.

Money was supposed to measure value. Somewhere along the way, it got a little self-important.

From Mercantile to Industrial to Financial Capitalism

The story of capitalism begins with mercantile capitalism, emerging in Europe from the late Middle Ages. City-states like Venice, Genoa, and Florence developed advanced trade networks, credit systems, and financial innovations such as double-entry bookkeeping and early banking structures. Mercantile capitalism was centred on commerce and exchange.

The Industrial Revolution (18th–19th centuries) marked a shift toward mechanisation, wage labour, and industrial production. Capital became increasingly abstracted from land and labour, emphasising returns and efficiency at scale.

In the 20th century, economist Milton Friedman formalised a new phase of capitalism: shareholder primacy. In The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits, Friedman argued that corporate managers’ primary responsibility is to maximise returns for shareholders, not broader societal outcomes.²

Scholarship on techno-feudalism argues that modern capitalism retains structural similarities to feudal systems: both concentrate power in a small elite, and both create hierarchies where the lower classes receive a disproportionately smaller share of benefits.³

Land stayed put. Money learned to conquer and became a social obsession.

Friedman and Shareholder Primacy: Turning Points in Value Measurement

Friedman did not invent profit-seeking, but he canonised it. By elevating shareholder value above all other corporate objectives, he elevated money from a tool into the scoreboard by which success is judged. Externalities like employee well-being, environmental cost, and human time were treated as irrelevant to the score.

This single-metric focus made systems efficient at accumulating money but inefficient at sustaining human or ecological life. In effect, money became both ruler and master, divorced from the realities of those whose labour it measured. Inclusive capitalism exists largely as a corrective: an attempt to put the amputated limbs of human and social value back on the economic body.

Growing up during the Great Depression understandably makes money feel like oxygen. The problem starts when you try to breathe it alone.

The Current State: Asset Inflation, Inequality, and the Moving Carrot

Modern capitalism does not just reward ownership; it inflates the value of ownership faster than the value of labour or productivity. According to research from the McKinsey Global Institute, global wealth is approximately $600 trillion, Yet much of its growth over the past two decades has come not from real investment but from asset price inflation. More than a third of the increase in wealth since 2000 consists of valuation gains detached from the real economy; only about 30 percent reflects genuine productive investment.⁴

This creates a moving carrot economy: wages stagnate relative to asset prices, making financial independence increasingly unattainable for those without existing wealth. Individuals labour more hours and save more diligently, yet the price of housing, equities, and capital-linked assets continually outpaces their gains. Effort, diligence, and saving are no longer sufficient pathways to economic security or upward mobility; ownership matters more.

As Isaac Asimov observed,

“The saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.”⁵

In economic terms, this means that financial innovation and market complexity have outpaced society’s ability to govern them in ways that produce equitable outcomes.

This dynamic is destabilising because money, when detached from real productivity and life outcomes, no longer measures what it is supposed to. The system rewards speculation and price appreciation, not contribution or human flourishing. The result is inequality, precarity, and a sense that the rules of the game are fundamentally rigged.

The carrot is always visible. Financial freedom remains a mirage.

Inclusive Capitalism in Practice: The Spine of Reform

Inclusive capitalism reframes value to include employees, communities, environmental health, and long-term outcomes alongside financial returns. It is not a utopian dream; it is a practical framework for correcting distortions created by singularly profit-oriented capitalism.

Bo Burlingham’s Small Giants: Companies That Choose to Be Great Instead of Big documents examples of companies that deliberately reject relentless growth in favour of purpose, community, and quality.⁶ These firms remain profitable while prioritising meaningful outcomes like employee well-being and strong local impact.

Inclusive capitalism thus provides a roadmap for embedding time, well-being, and sustainability as formal metrics rather than afterthoughts.

Turns out “bigger” is not the same as “better.” Who knew, besides furniture makers?

Time as Value: Operationalising a New Nominator

Time is finite; money is not. That simple fact makes time a more reliable anchor for value in human-centred systems. Valuing time does not mean abolishing money, but rather co-nominating it alongside money.

- Redefining productivity: Outcomes and human experience over hours worked or profits extracted.

- Economic redistribution: Time is inherently egalitarian. Everyone has the same 24 hours in a day.

- Shifting power dynamics: Roles that are time-intensive but undervalued (e.g., caregiving, education) gain equitable recognition.

- Well-being focus: Societal goals shift toward free time, creativity, and personal development over relentless growth.

Challenges include the subjectivity of time’s value, economic disruption of industries reliant on low-wage labour, and cultural resistance rooted in norms that equate worth with money.

Central banks can print money. They have been remarkably unsuccessful at printing Sundays.

Historical and Contemporary Perspectives Supporting Time-Based Value

A range of thinkers and movements have anticipated the logic of valuing time:

- Karl Marx: Labour Theory of Value emphasises labour time as central to wealth creation and highlights exploitation.⁷

- John Maynard Keynes: Predicted reduced work hours through productivity advances, allowing societies to prioritise leisure and well-being.⁸

- Bertrand Russell: Advocated for shorter work hours to improve happiness and intellectual engagement.⁹

- Albert Einstein: In The World As I See It, he argued that people should not be bound by the demands of capitalism but should have time for creativity and reflection.¹⁰

- Universal Basic Income movement: Redistributes economic freedom to free up individual time for non-survival pursuits.

- 4-Day Workweek initiatives: Demonstrate measurable productivity gains and improved employee well-being.

- Degrowth movement: Prioritises sustainability and quality of life over endless economic expansion.¹¹

Turns out humans like having time for things besides work. Who could have guessed?

Phased Implementation: From Inclusive Capitalism to Time-Based Value

A realistic strategy for institutionalising time as value within inclusive capitalism could unfold in phases:

- Measurement: Track time invested and its qualitative impact across stakeholder groups.

- Progressive policies: Implement living wages, flexible hours, and equitable resource distribution.

- Cultural shift: Normalise prioritising well-being, leisure, and sustainability in economic decisions.

Inclusive capitalism acts as a transitional framework, embedding time and human-centred metrics without destabilising societies or economies overnight.

Changing culture is hard. Especially when everyone is busy making money instead of noticing.

Limits, Risks, and the Honest End

Inclusive capitalism and time-based value are not cure-alls. Time can still be unequally distributed, and corporate adoption of “inclusive” language may be superficial. Cultural resistance to moving away from money-centric norms will be significant.

Yet doing nothing is not neutral; it sustains a system where money dominates and human experience is sidelined. Inclusive capitalism does not eliminate trade-offs, but it reframes the essential question: what counts as value, and who gets to decide?

If capitalism wants to survive, it may have to learn the radical idea that people are not a rounding error.

Disclaimer

Part of the research, all rephrasing, and structuring of this article was done with ChatGPT. The ideas are quasi-original, as well as their associations; I just chose the “stochastic parrot” to put it in a readable format you’d appreciate. It’s what it is good at. What it lacks is the understanding of the feelings, words and connotations triggered, as well as causalistic reasoning and feelings-based decision-making. But perhaps that will follow in a later post.

Nevertheless, the need for change, the need for inclusive capitalism, is even more acute in the AI-fueled era.

References

- Wilson, Edward O., The Real Problem of Humanity.

- Friedman, Milton. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits, The New York Times Magazine, 1970.

- Techno-Feudalism and the Tragedy of the Commons, berlinartprize.com.

- McKinsey Global Institute. Out of Balance: What’s Next for Growth, Wealth, and Debt? (2025).

- Asimov, Isaac. Quoted in context about science vs. wisdom.

- Burlingham, Bo. Small Giants: Companies That Choose to Be Great Instead of Big.

- Marx, Karl. Capital: Critique of Political Economy.

- Keynes, John Maynard. Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren, 1930.

- Russell, Bertrand. In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays.

- Einstein, Albert. The World As I See It.

- Latouche, Serge. Degrowth: Vocabulary for a New Era.